Neuroevolution in squids

24 Apr 2020Evolving a neural network

Artificial neural networks mimic real biological nervous systems. They contain neurons and connections between them to transform input signals into meaningful output. In the field of machine learning, these networks are often initialized with random connections between the neurons, after which the network is trained until it behaves in a useful way. This works well enough, but many simple nervous systems found in animals work "out of the box"; no one teaches a fish to swim or butterflies to fly, even though their behaviour is produced by networks of neurons. Their nervous systems are not products of random initialization and subsequent training, but of evolution. After many generations, nature has produced an arrangement of cells and connections producing complex and useful behaviour.

To produce neural networks that produce non-learned behaviour, neuroevolution can be used. Evolutionary algorithms (like the one I used to evolve plants) evolve a genetic code over time. The genetic code (a model for DNA) and the organism it represents starts out very simple, but over the course of many generations small mutations add beneficial complexity and functions promoting further propagation of these properties.

Digital squids

To demonstrate neuroevolution, I want to evolve digital squids. The squids have the following properties:

- They can have any number of tentacles with varying length.

- Each arm is controlled by a single output neuron, swinging them to one direction when low output is produced and in the opposite direction when high output is produced.

- Squids have heads, the size of the head determines the amount of neurons it may have.

- The mass of a squid is determined by its head size and number of tentacle segments.

- Squids swim in simulated liquid filled with dots representing food. Touching these dots "eats" them, and the score of a squid is the number of dots it eats divided by its mass.

These properties should through evolution produce squids that can swim efficiently through an environment, eating as much food as possible. Because they have mass as well, squid bodies must be effective: heavy bodies and big tentacles require more food, there must be a good reason to evolve them.

Because the squid can have varying properties (like head size and the configuration of its tentacles), these properties evolve as well. The DNA of a squid does not only contain the blueprint for its brain, but also its body plan.

Figure 1 shows a simulated squid with two arms. The curling motion of the arms is achieved by adding a spring strength to the arm segments; if the muscles would stop moving the arms, the segments would slowly align until the arms are straight lines. To calculate the amount of acceleration, all lateral motion is summed. In the figure, all the sideways motion of the red lines would make up this number. By swinging tentacles behind its body, the squid achieves forward motion.

Spiking neural networks

Choosing the right neural network for the job at hand is tricky. There are many different flavours of neural networks, this chart contains a nice overview of some of them. The neural networks controlling the squids are in some aspects not like most well known networks:

- They do not have a traditional input to output structure. In fact, they do not need to contain input neurons at all. While many traditional neural networks transform or classify input in a way, the squid networks should produce behaviour.

- The squid neurons need to work in real-time. There is no question to answer structure, the networks should function continually.

- Because the networks evolve over time, they have no preset structure or size. The number of neurons and the number of connections between them varies according to their DNA, and changes over generations.

A spiking neural network fits these requirements. They operate in real-time, and were designed to mimic nature more closely. Just like real neurons, cells in a spiking neural network build up potential gathered from all its inputs over time, and slowly return to their "neutral" state when no input is received. Spiking neural networks do not need to adhere to a strict connectivity scheme. They consist of a layer of input neurons, a layer of output neurons (controlling the tentacles in our case) and a number of neurons in between, called the hidden layer. Neurons in the hidden layer may be connected to input and output neurons, but neurons may be disconnected as well. For this application, neurons within the hidden layer may be connected to each other.

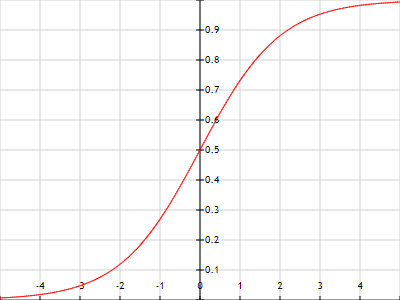

The neurons in the nervous systems all have an activation function. This function determines the output value of the neuron based on the sum of its inputs. Neurons are connected by axons, which connect a source to a target neuron. The axon adds the source output value multiplied by the axon weight (which can be a positive or negative number) to the target activation. The activation function then determines the neuron output based on its activation. The chosen activation function in this simulation is the logistic function:

$$\frac{1}{1+e^{-a}}$$

In this equation, $a$ is the activation of the neuron. Figure 2 shows a plot of the function. When $a=0$, the output is $0.5$; this is useful in this simulation, because the network must be able to produce behaviour even when no input is given. If the default output is non zero, some signals always flow through the system. The value of $a$ can in theory be very small or very large, but the asymptotes of the logistic function ensure that the output value is always in the range $[0, 1]$. In this way, extreme output values will not propagate through the system.

Simulating evolution

The simulation environment consists of the following components:

- Any number of squids with varying body plans and a spiking neural network to control its limbs.

- Food scattered around the environment.

To start simulating evolution, the simulation simulates a fixed amount of time per generation. In my simulations, I chose time periods of 20 to 30 seconds. After this time, the best performing squid is picked and duplicated several times to form a new generation of squids. Before the next simulation takes place, all squids are mutated slightly. The following properties may mutate:

- Body radius, and with that the maximum number of allowed neurons in the squid brain.

- The number and location of tentacles.

- The length of the tentacles.

- The number of neurons in the brain.

- The axon connections between the neurons (connections may appear and disappear, and connection weights may increase or decrease).

For now, the squid brains contain no input neurons. The number of output neurons is always equal to the number of tentacles, and every tentacle is assigned one output neuron. When a tentacle mutates away, its corresponding output neuron is deleted as well. When a new tentacle is mutated, it receives a new randomly connected output neuron.

The source code for the simulation is on GitHub, and the simulation runs in a browser.

Results

Running the simulation usually results in moving squids within several hundreds of generations. When a working swimming strategy evolves, it will usually evolve into the most optimal version of itself over time.

The nervous systems can be visualized. Figure 3 shows a simple nervous system of a squid with two arms. The network contains five neurons represented by orange dots, and two output neurons represented by blue dots. When neuron output rises, neurons be come more colourful. When output decreases, the dots become transparent. Axons are visualized by dotted lines between the neurons they connect. When an axon transports a signal (and influences the target neuron), the dotted line becomes more visible while the dots move in the signal direction.

Figure 4 shows several squids swimming around in a simulation environment. These squids swim using two tentacles that swing simultaneously. Some variety among the agents can be seen:

- Tentacle length varies, but their movement patterns are roughly equal.

- Two agents in the lower half have evolved extra tentacles that don't do much at this point. They will add mass to the squid, making them perform worse.

Conclusion

The simulation at its current state demonstrates the effectiveness of neuroevolution, and forms a basis for several extensions:

- Sensors may be added to the squids. One or more eyes could produce signals that may steer a squid towards food sources or away from competitors.

- Other output organs could be created as well. Simple arms could move or push food around, and ink sacs can cloud the vision of nosy competitors.

- Larger environments can be created where squids only reproduce in their neighbourhood to allow multiple different species to evolve and exist simultaneously.

- Generations can be simulated for longer periods of time. Currently, the behaviour can be interpreted as a race to get all the food quickly and efficiently. This requires speed, but no complex maneuvers. If food grows over time, or moves with a current, much more elaborate strategies are required.

These additions would not require any changes to the basic mechanism of neuroevolution, they just allow for more different strategies to emerge. The versatility and adaptivity of the demonstrated neuroevolution framework makes it an interesting tool for many other applications, especially those focusing on artificial life.