Swarm behaviour

1 Feb 2018Simulating swarms

When the developers of the latest Call of Duty game in 2013 enthusiastically announced their state of the art "fish AI", they were ridiculed. After all, even the 1996 title Super Mario 64 featured fish reacting to their environments. While I can totally appreciate details like realistic animal behaviour in games, it should be said that simulating schooling behaviour is not that ground breaking. The algorithms are simpler than the emergent behaviour makes it seem. That does not make the applications less interesting though, and there are many.

Swarming frequently occurs in nature. Animals often benefit from it because it offers them increased protection from predators, or it may help them follow the rest of the group to a destination. To name some common examples:

- Fish schooling

- Birds flocking

- Ants crawling

- Cattle herding

Many simple animals seem to create complex flocking patterns, but the same behaviour is also seen in complex animals. Crowds of humans show swarming behaviour too, and simulating this behaviour can help design spaces that are suitable for crowds. A designer may design a space in such a way that the crowd follows a general path, or a design can be devised to maximize throughput. Another application is simulating the time it takes for a large number of people to evacuate a space. In this article, I walk through the process of creating a simple swarming algorithm.

Boids

One of the first algorithms for flocking called Boids was made by Craig Reynolds in 1986. The simulation I have implemented mostly follows his design. In this algorithm, every agent determines how it should move or steer by itself. Agents have a limited view of the world around them, and their behaviour is determined by what they sense. The goal of the algorithm is to make agents stay together, without touching or colliding too much and without the group falling apart. This is accomplished by using three different sensing areas which trigger three kinds of behaviour.

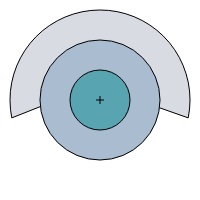

Figure 2 shows the sensing areas of an agent. The three colored zones around the agent center will tell the agent when other agents are detected in that area. The behaviour an agent will show depends on the zone other agents are detected in. The three zones have three different effects:

- The area closest to the agent is the repulsion zone. When agents are in each others repulsion zone, they will move away from each other. This zone could be analogous to touch or very close proximity; schooling fish for example will try not to touch each other by staying out of this zone.

- The ring around the repulsion zone is the alignment zone. If agents are in each others alignment zone, they will both steer to match each others direction; they want to stay together, and moving into the same direction will accomplish that. Once agents are aligned, little steering is required.

- The outer ring is called the attraction zone. If an agent detects another agent in the attraction zone, it will steer towards that agent in order to follow it. I have limited this zone by a certain angle to simulate the field of view of eyes. An agent won't usually steer towards agents behind it, because it doesn't have eyes in its back.

When agents apply the three simple rules above, seemingly complex behaviour emerges. The implementation can be tested below, and its javascript source can be found here. The effect of all parameters is explained below.

| Agents: | ||

| Agent speed: | ||

| Repulsion zone: | ||

| Alignment zone: | ||

| Attraction zone: | ||

| Attraction angle: | ||

| Repulsion force: | ||

| Alignment force: | ||

| Attraction force: | ||

| Gravitation force |

The application above has a number of parameters which influence agent behaviour.

- Agent speed determines the minimum speed of an agent; an agent that does not experience any influence will move with this speed.

- Repulsion, alignment and attraction zone determine the radii of the aforementioned zones. These add up to each other.

- The attraction angle determines the angle of an agents field of view in degrees.

- The forces determine the magnitude of influences. For example, if an agent has another agent in its repulsion zone, its velocity will move away from the other agent with a magnitude of Repulsion force. The force is added every time an agent is encountered, so the more agents, the more force is added.

- Gravitation force determines the force that will be added in the direction of the view center. This makes sure all agents move towards the center, which makes larger groups of agents turn as a whole.

To sum it all up, the velocity of an agent is updated using the following formula:

$$\vec{v_{next}} = |\vec{v}| * s + \sum_{n=1}^{rc} |\vec{r_n}| * f_r + \sum_{n=1}^{ac} |\vec{a_n}| * f_a + \sum_{n=1}^{tc} |\vec{t_n}| * f_t$$

where $\vec{v}$ is velocity, $s$ is agent speed, $rc$, $ac$ and $tc$ are repulsion, alignment and attraction agent counts respectively. $\vec{r_x}$, $\vec{a_x}$ and $\vec{t_x}$ denote the $x^{th}$ vector in the influence directions of repulsion, alignment and attraction respectively, and $f_r$, $f_a$ and $f_t$ are the forces appointed to repulsion, alignment and attraction. In the example above, gravitation force is added. This is not incorporated in the formula.

This function could of course be applied to any number of dimensions. The simulation above is 2D, but moving it to 3D is trivial once good rules have been established.

It is worth mentioning that the time complexity of my algorithm is $O(n^2)$, because I check the distance between every pair of agents once. For very large swarms, additional optimization would be required. A naive implementation might let every agent check against every other agent, but this results in many redundant checks because pairs will be evaluated twice.

Conclusion

While fish AI is an interesting use of swarm behaviour, there are many more useful applications. One could think of simulations that help with optimizing crowd flow, traffic management in a city or building layout design. Another use could be drone flocking behaviour; if drones need to stay together, flocking behaviour could be a property borrowed from nature like many other natural principles that are applied to technology. For these applications, the example above needs to be expanded. There are many possible additions:

- Obstacle avoidance

- When no other agents can be detected, an agent could look further away

- Influence from weather conditions

- Different types of agents, some could be more influential than others

- Predators driving the flock apart

- Signals that agents could pass on to their neighbours

I have released the source code on GitHub under the MIT license.